Brice Dellsperger - Body Double X (2000)

Monday, March 17, 2008

Download this at KaraGarga.

Body Double (X)

Maxime Matray

– C’est pas maintenant que vous sortez votre liqueur médiévale ?

– C’est pas là que vous me traînez par les cheveux jusqu’au lit ?

– You supposed to take out your medieval liquor now

– You supposed to grab my hair and drag me to bed now?

Fabio Testi and Romy Schneider

L’important c’est d’aimer

Life in the gallery of replicas

For several years now,Brice Dellsperger has been an expert in the art of faking in the most blatant respect: he remakes and recycles specific movie scenes. The first episodes of his series of palimpsests, entitled Body Double, add a subversive cosmetic layer to the original sources, turning them inside out and allowing them to span several genres. The source material includes carefully selected pieces from the works of Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho), Brian de Palma (Dressed to Kill, Body Double, Blow Out, Obsession), Georges Lucas (Return of the Jedi), and Gus Van Sant (My Own Private Idaho). However, every last vicissitude of the linear narratives of these films has been meticulously removed, with a nearly surgical care, so that in the end each one of these sequences seems to harbor within itself, and for itself, something immediately archetypal. Though designed as a fictional shortcut, each sequence is always shown outside the boundaries of fiction. Murder scenes – three in total, one by strangulation and others through a wide range of injuries – a love scene set on a romantic seashore, a chase scene set in an amusement park, a homecoming scene set in an airport, a tragic scene with fireworks as a backdrop, a confessional scene with oedipal and incestuous overtones, a night drive set to disco music, and so on. Systematically, the viewer finds that the same cinematic turns consistently allow the filmmaker to attain the same effects. For the sake of the remake, each gesture, each shot, and each expression have been dissected in depth before being brought into play again in a new and synthetic context. Sometimes, the same sequence has been shot and edited several times with different actors. This could indicate the beginnings of a sort of checklist of passions and actions shown in an over-simplified way, for the use of proto-filmmakers and crypto-Hollywood freaks and their emulators. However, in the end, you find yourself in a totally different dimension. Because most of the characters born from Brice Dellsperger’s mind are men wearing wigs, fake boobs, make up, and gaudy women’s apparel. Within the confines of our traditional lexicon, we would name them “transvestites,” which is somewhat of a definition, but still falls short. These characters sometimes play multiple roles, in dialogue with their alter-egos, crowned with incredibly huge masses of fake hair of all hues and shapes. If we ignore the considerable weight of this anecdote, these scenes are often a chance to portray the ideas of otherness and the concept of twins or doubles, and the relationship that each and every one of us has with death, perched atop too high-heels. And indeed, Death often appears like this.

What counts is appreciating the extension

Better say it before someone gives us grief: Body Double (X), opus number 10, has nothing to do with a tribute. It is a palimpsest, a dubbing act; or maybe merely a painting in all its grandeur on a second-hand canvas scavenged from an old garbage can. At its origins, the film is bloody; beginning and ending with scenes of bloodshed. The former is very obviously fake. The latter is, too, (though in a less blatant way), this is, after all, a movie, but if we believe in the veracity of film and its prerogatives, we necessarily believe in the veracity of this cinematic blood. In the space between these two bloody sequences, a complex narrative thread unravels, woven with unsure feelings and vague intensions, business deals and failures. Quite a few failures. Notably, one actress learns to say “I love you.” People die. It is a movie by Andrzej Zulawski, based on Christopher Frank’s novel La nuit américaine, starring Romy Schneider, Fabio Testi, Jacques Dutronc, Klaus Kinski and a few other actors.L’important, ce n’est pas d’aimer le film de Zulawski. What matters is not whether or not you like Zulawski’s film. You can even watch the enhanced version produced by Brice Dellsperger without knowing anything of the original.

Opinions shared with the common people

“No one will believe you if you claim it is a remake”. Indeed, Dellsperger’s films are too far removed from their sources to be considered remakes. Regarding the Body Double series, Brice Dellsperger stated: “Our aim was to empty out the fiction, to drain all the energy from the original movies, so they would become just empty shells.’’ Therefore, each component was traced, re-considered, re-thought and re-shaped separately not so much to meet an independent narrative requirement, but rather to offer the viewer the solidity of a conglomerate composite. This film is a piece of particle board glued together by a cabinet-maker. It is a mongrel dog that has constructed itself from the ground up, legs, back, and hide, then teaching itself its own vocabulary. You always walk better when you start by building your own legs, even when treading on the cast-off limbs of your forebears. This is a well-known fact. There is not a single dog that would dare to refute this. Not even a single dog’s armature.

On a practical level, what Brice Dellsperger does is essentially touch-up work: he applies a slight layer of make-up to the framework using paintbrushes loaded with excess and overflow; which lends the whole piece a brand new hue, rouged cheeks and a bit more formality overall. Sometimes, something reminiscent of the Ancien Régime (still wriggling underneath the water’s surface, as discreet as hot lava) pierces through the cosmetic crust. And this emergence gives life to hills and valleys, as well as many discrepancies, some noises, and a smile. One does not know how to get rid of it; or even if one should get rid of it. Let’s keep it, then, because this sprucing up, and the resulting bumps and creases in the make-up, all converge towards painting and its pointless, modernist pursuit of a smooth, flawless surface. Brice Dellsperger’s method is based on stratification, superposition of shots and collage of vignettes. Resorting to the power of thickness, he exhausts the image so as to transform these layers something abstract. Take a look at the image: its sole purpose seems to be continuing to signify what it has always signified. Poor thing. But it will soon give up as the significance is buried deeper and deeper under each layer. However, it will resurface somewhere else, transformed, worn out and magnified all at once. It resurfaces within the margins, through the presence of these heavily made-up characters showing too much cleavage and perched on excessively high heels.

All these potentially grotesque elements that strike us from the first moments of the film fade away very quickly as the eye becomes accustomed to them. All that remains, then, is the astonishing tipsiness elicited by the formal elements of the film: the flickering of the screen and the inability of the gaze to settle on any real object. That is, on any object other than the figure of the transvestite, vital element in all of Brice Dellsperger’s works, and a figure belonging to no defined dramatic category. Just like the figure of the clown as defined by Christian Baud-Mercier in his Ennui Spectaculaire, the transvestite has this “perfectly measured taste for nearly tragic emphasis, conveyed by face paint, onomatopoeias, and a wide range of provocative gestures […] nobody has asked him for the moon; yet he brings it back anyway. But, as always, it is made out of cardboard.”

What do I look like?

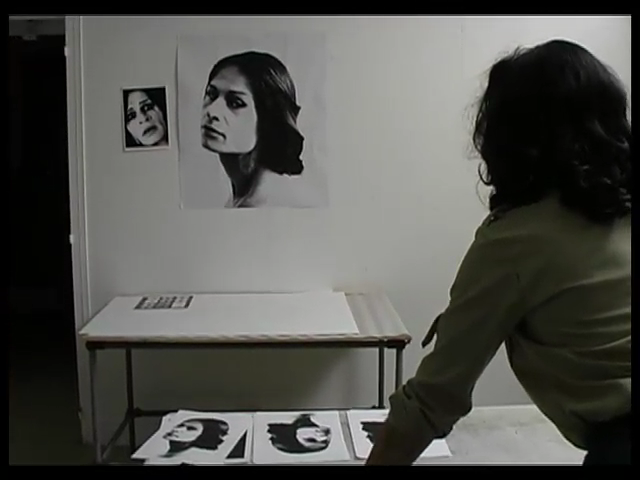

Needless to say, Body Double (X) is a complex and ever-changing fortress, and the machinery behind all this is called Jean-Luc Verna. He plays every single part. His duplicity is made obvious through his many hairpieces and garments, which change at the whim of his characters. One recognizes his arms, his hands dotted with constellations enhancing their smooth and soft appearance.

During the course of the film, he is his only interlocutor, under the weight of his various eclectic hairdos. Sometimes represented by a half-funeral latex mask of his own face, he gives himself his cues. At other times, exploring the far reaches of the vast territory of acting, he speaks to no living creature. Several times he resorts to simultaneous, lip-synched monologues.

Jean-Luc Verna is the nucleus around which revolves the setting of this drama already compromised by others, at an earlier time. Take a look at these tables, these removable carpets, these mobile fireplaces, all playing off the actors’ movements. The bodies move as if they were weightless. Both furniture and people seem permanently caught up in subsidiary torments, in weird, asynchronous states of confusion. In the end, there remains but one distinguishable element: Jean-Luc Verna acting the whole movie for his own sake, for the film’s sake, through and through to its basest elements.

No pictures, please

Andrzej Zulawski’s L’important c’est d’aimer tells the tale of individual cowardice caught within the grander scheme of universal cowardice, and the attempt to sort out one from the other. Amidst rampant conflicts of interest, only one character seems to remain truly lucid: the part played by Michel Robin. Before feverishly climbing upon a table, he tells Servais Mont (played by Fabio Testi): “Come on, let’s be realistic. We’re in the Western world, the solution will be a capitalistic one. How much do you love your cute little actress?” Brice Dellsperger’s adaptation manages to exclude this enlightening scene, in which lies the entire moral core of Zulawski’s film, without compromising his film’s artistic integrity. This is, undoubtedly, because the moral and edifying aspects of Zulawski’s film have, themselves, been annulled. Along with all traces of pathos. Gone with the wind.

The whole “Body Double” series takes root in this very territory. A body double, in English, is someone’s stand-in. But if we look at the concept very literally, as in “two bodies,” it describes so well what it is Brice Dellsperger aims to produce: the impression that there is, thanks to these added cosmetic layers, more than a body. This way, he can – as he recently stated in a Parisian newspaper interview– “lend some texture and roughness to the image”. And vice-versa.

Download this at KaraGarga.

Download this at KaraGarga.

at 7:24 PM